There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

{{8/04/2022}}

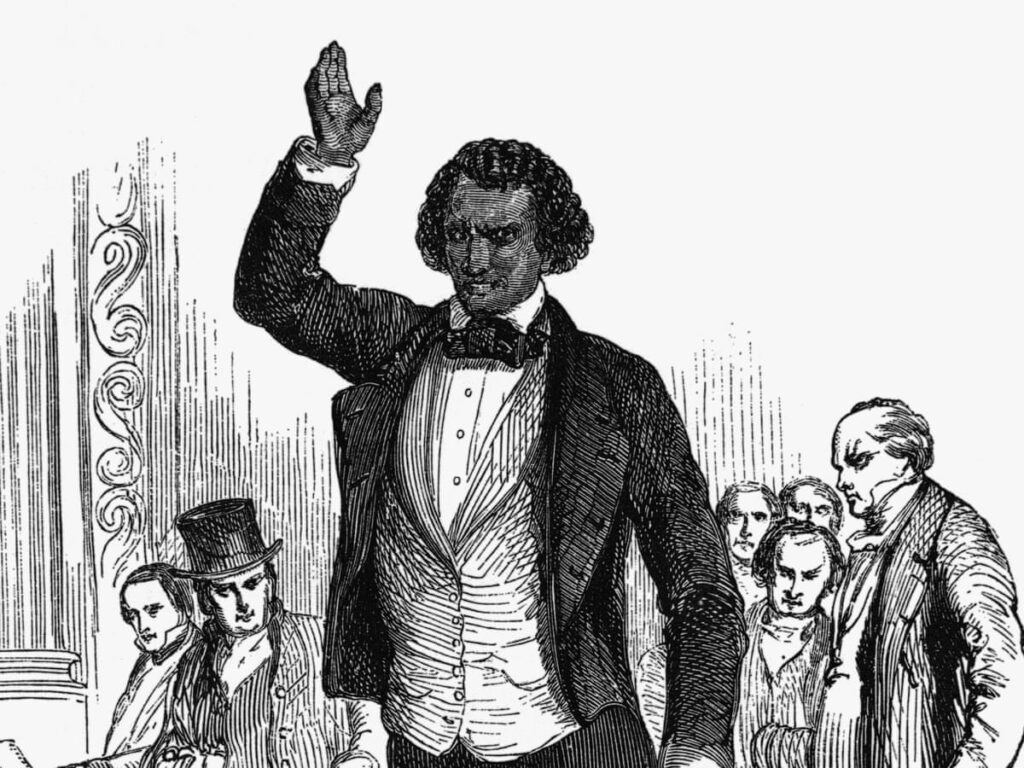

Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery to become one of the leading intellectuals of his time. He advised presidents and lectured to audiences numbering in the thousands on a wide range of causes.

Douglass wrote several versions of his autobiography that detailed his experiences in slavery and his life after the Civil War. One of his more well-known works is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. On July 5th, 1852, Douglass gave a now-famous speech commemorating the birth of the United States in which he contrasted the founding of the nation with its practice of slavery.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery in approximately 1818, in Talbot County, Maryland. As was common for many born into slavery, the exact date of Douglass’ birth is not known. However, Douglass did later choose to celebrate his birthday on February 14th. While at first Douglass lived with his maternal grandmother, he was later chosen to live with one of the plantation owners. Douglass’ mother had a sparse presence in his life, and died when he was just ten.

Sophia Auld, the wife of Baltimore slave-owner Hugh Auld, taught the twelve year old Douglass the alphabet, in spite of a ban on teaching slaves to read and write. When Hugh Auld forbade his wife from teaching the boy, Douglass kept learning to read and write from white children and from others in the neighborhood.

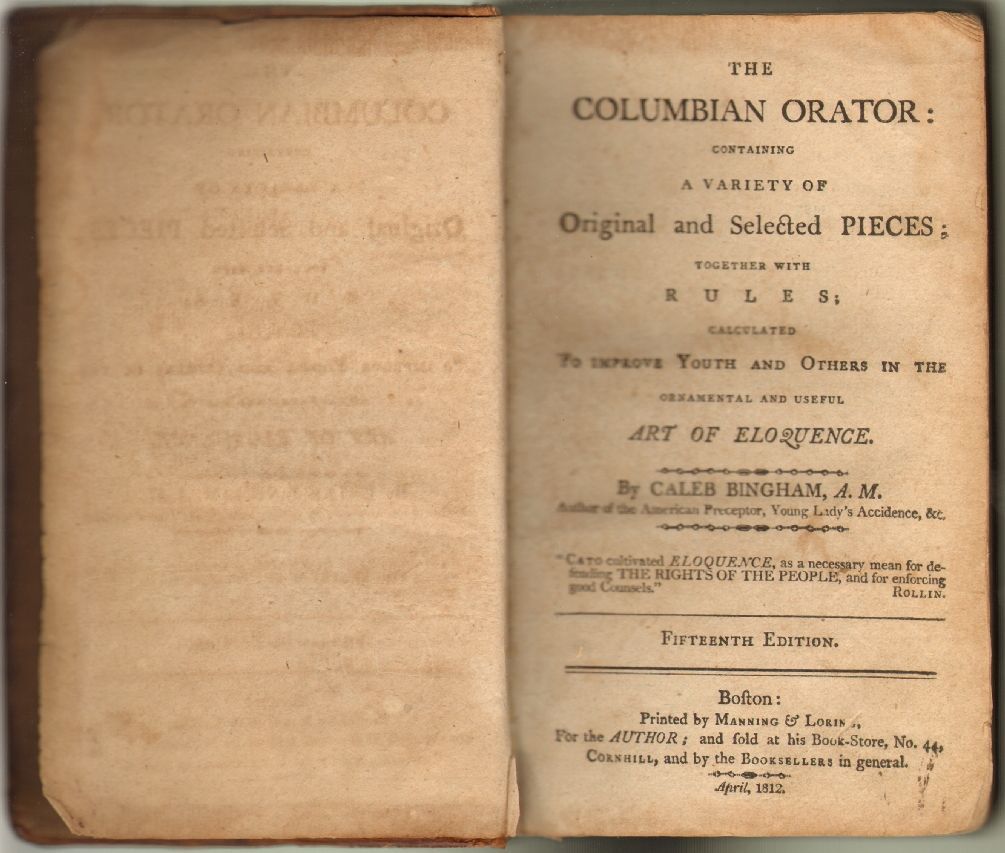

The young Douglass was a voracious reader. He often read newspapers and was an avid reader of literature and political writing. Douglass’ opposition to slavery began to take shape thanks in part to the many and wide-ranging works that he read. Later in his life, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator with helping to define his views on human rights.

Douglass longed to share his ever-growing knowledge with other enslaved people. He began to teach other slaves to read the New Testament of the Bible at a weekly church service. Interest in Douglass’ lessons was so great that more than 40 students would attend the lesson each week. The other slave-owners soon got wind of Douglass’ teaching though, and came to the lesson one week armed with clubs and stones, thus putting an end to the weekly lessons.

At age sixteen, Douglass was sent to work for Edward Covey, who was known as a “slave-breaker.” Covey’s physical and psychological abuse nearly broke the young Douglass. The young boy began to fight back though, and when Covey attacked him one day, Douglass fought back and physically defeated Covey. From this moment onward, Covey never again attacked the young Douglass.

Douglass began to look for ways to escape his slavery. On September 3, 1838, Douglass boarded a train bound for Havre de Grace Maryland. He was wearing a sailors uniform that had been given to him by Anna Murray, his future wife, and he carried identification papers that had been given to him by a free Black sailor. Less than 24 hours later, Douglass arrived at the safe house of New York abolitionist David Ruggles.

Douglas fell in love with Anna Murray and married her in New York soon after he had arrived. The couple eventually adopted the name Douglass in order to disguise Frederick’s identity. They moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, which had a strong free Black community. After settling in New Bedford, Frederick and Anna had five children together: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Redmond, and Annie, who died when she was just ten.

After Anna died, Douglass remarried Helen Pitts, who was a feminist from New York state. Pitts was a graduate of Mount Holyoke College, who shared many of Douglass’ principles concerning human rights. The marriage of Douglass and Pitts was a controversial one at the time, since Pitts was white and was twenty years younger than Douglass.

Once he settled with Anna in New Bedford, Douglass was frequently asked to tell about his experience in slavery at abolitionist (abolishing or getting rid of slavery) meetings. Douglass’ strength and rhetorical skill made him a frequent speaker at such meetings and prompted the founder of the weekly journal The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison to write of Douglass in his newspaper. A few days after the story ran, Douglass gave his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s annual convention. Douglass was speech was such a success that he was asked to give a lecture tour throughout the northern states.

After spending some years on his lecture tour, and in Europe (during which he became a free man), Douglass settled back in New Bedford, where he regularly attended a Black church and continued to subscribe to The Liberator. Urged by Garrison to write about his life as a slave, Douglass wrote and published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave in 1845. The book became a bestseller in the United States and was published in several European languages.

Douglass was one of the most famous Black men in America at the time of the Civil War. Douglass made use of his fame to advocate for the role of African Americans in the war and their status in the United States. Douglass consulted with President Abraham Lincoln on the treatment of Black soldiers and later with President Andrew Johnson on the issue of Black Suffrage (the right to vote).

After the war, Douglass was appointed to several political positions. Douglass served as President of the Freedman’s Savings Bank and as chargé d’affaires for the Dominican Republic. He was later appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti. This was post that Douglass held from 1889-1891.

Frederick Douglass died of a heart attack or stroke on February 20, 1895, shortly after returning from a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington D.C. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

On July 5th, 1852, Douglass addressed a crowd at the Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York. The crowd had gathered for an event that commemorated the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Douglass began his speech by praising the forefathers of the United States, saying that “It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men.”

Douglass then went on to contrast the founding of the nation, and the principles of its founding, to the practice of slavery, asking “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days of the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” Douglass’ words were a firm reminder that the United States still had not yet achieved “liberty and justice for all.”

{{Brett M.}}

Founder of LingoMetro, Brett lives in Seattle with his wife and his cat, Tippee.